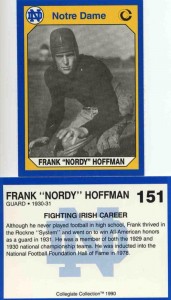

(Notre Dame Football News | by Scott Engler) – I recently ran into a Domer who told me the story of “Nordy”. Far before Rudy, Frank Hoffman was part of Irish lore from the Rockne days. A member of the Hall of Fame and All-American, Nordy had never played football… until one day, walking across campus, he met Knute. Nordy eventually moved on to Washington DC where, as Sergeant-at-Arms of the Senate, he became a gateway for Notre Dame grads into the world of Politics.

(Notre Dame Football News | by Scott Engler) – I recently ran into a Domer who told me the story of “Nordy”. Far before Rudy, Frank Hoffman was part of Irish lore from the Rockne days. A member of the Hall of Fame and All-American, Nordy had never played football… until one day, walking across campus, he met Knute. Nordy eventually moved on to Washington DC where, as Sergeant-at-Arms of the Senate, he became a gateway for Notre Dame grads into the world of Politics.

How He Came to Notre Dame

I am a child of the Depression. I saw it first hand, and I wish to God I never had to see it because it was so difficult for so many people. I was lucky. My grandfather had some money. I went to college. I went to Notre Dame–I was going to go to Stanford, and then my cousin, who was in the business, said, “Why don’t you go East?”

Yes, I had really registered at Stanford, and my cousin said, “Why don’t you go East?” He had just come back from Wharton School at Penn (University of Pennsylvania), and he said, “Don’t go there, it’s downtown. Get a place where there’s a campus.” My grandfather knew a man who was teaching at Notre Dame in the law school. He asked me, “Would you like to go there?” I said, “I don’t care.” I wasn’t crazy about the football thing, because I didn’t understand enough about it then. But I said, “I’d like to go.”

They looked it up and found out that it was rated highly for education, and I wound up by my grandfather and grandmother taking me back on the train. In those days you only had trains, no airplanes, so I went to the University of Notre Dame and graduated from Law School there, but it was a combined course of commerce and law, a six year course.

It was a marvelous experience, having gone there.

Meeting Knute

I was walking across the campus one day and I ran into a fellow by the name of Knute Rockne. Well, I was a freshman, and I don’t think anybody understands this, but talking to Knute Rockne in those days was like talking to God. He looked at my size and invited me to try out for his team. This was my induction into football.

Later I was made an All-American and then inducted into the Hall of Fame. And that’s the greatest claim to fame that I have, because here I had never played the game, and then I learned the game from him and played for a university that never lost a game in two years, in two different seasons.

And here is a picture of Notre Dame, what it looked like in those days. /Points to aerial photograph on the wall/ I stayed right here in the freshman hall. It’s no longer on the campus. There was sophomore hall. That was the University of Notre Dame in 1927-’28. That’s the old stadium that burnt down, and they built a new stadium. In 1929 we were traveling. But that was the University that I went to. It has two lakes, and St. Mary’s is over there. It doesn’t look the same now.

What I went out for was track first. The reason I did was because I was a manager, and I was asked to roll the shot-put back to the shot-putters, Joe Repetti and another guy who were putting the shot out. I watched them for about a week, and I thought it was silly to roll it back, so I put the shot back–having watched them back–and I put it at least six feet farther than they were doing it. The coach found out about this, and the next thing I had a uniform on. Well, they taught me how to run, they taught me how to put the shot. So I was out for track and made my letters, three letters in track. I made two letters in football. But the point was that I had learned how to run by the time I played football.

First I was a tackle, and then they transferred me to guard in 1931, before Rockne was killed. Having learned to run, and all those things that led up to it, probably gave me a step up over other people who hadn’t had that kind of training. And motivation. The whole thing in life is motivation. If you’re motivated, you’re going to do it. This was new to me. Ted Toomey, who used to be one of our great tackles, was talking about this one time when I was making a speech. He said, “I want to tell you about this guy; this young man, when you looked in his eyes, he had the most piercing eyes to watch everything you did, and then he would come back and do it.” He said, “That’s how he became motivated.” That’s what his whole theory was, and I think that whatever success I had was not me, it was the people who were teaching me.

I remember, my father came back to see my play one time, just once, the only time he was back there. He came from Seattle and he was going to New York, and on the way back from New York he stopped. We played somebody, and I intercepted a pass. I thought, “Oh, boy, and my dad saw me.” I returned the pass, oh, maybe twelve or fourteen yards, I didn’t get a touchdown or anything like that. Afterwards, we went out to dinner and I said, “Dad, did you see me intercept that pass?” He said, “Yeah.” I said, “What did you think about it.” He said, “You remind me of a cow pulling his foot out of the mud.” /Laughs/ Which was true, I suppose, from his perspective. That brought me down a peg or two.

But it was a great education to have been privileged to play for Notre Dame and for Rockne, and Hunk Anderson and the rest of the guys who were there. It lives with you forever. We meet every two years, the ’29-’30 team, Rock’s last team, we go out to the campus every two years to meet. In the old days we used to booze it up, now all of us are taking pills we don’t booze it up, but we have a great time because we have a rapport. Everybody said, “I never saw anything like you guys. You guys are absolutely nuts about each other.” We are. We have a tremendous respect for each other. I get letters from these guys all over the country, I write to them–and some of them don’t write back, but most of them do. It was part of a growing thing that went through my life, having that kind of people around you. They were all good people that worked hard, they were decent people.

I was back a couple of years ago, and a fellow came up to me in the Morris Inn and said, “You’re Nordy Hoffmann.” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “You’ve always been my hero.” I looked at him and said, “You’ve got to be sick. I’m you’re hero? What did I ever do?”

I was back a couple of years ago, and a fellow came up to me in the Morris Inn and said, “You’re Nordy Hoffmann.” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “You’ve always been my hero.” I looked at him and said, “You’ve got to be sick. I’m you’re hero? What did I ever do?”

He said, “When you were a freshman, you and Moon Mullins got arrested for keeping the Ku Klux Klan from going out in front of the campus.” I said, “Are you serious?” He said, “Yes, isn’t it true?” I said, “Yeah, it’s true. Moon and I did get arrested.” We were arrested for keeping the Ku Klux Klan from walking on our campus. They came up in masks, they were just walking right up Notre Dame Avenue. We met them and we took their masks off and everything else. I mean, we were playing for keeps. We were arrested and taken down to jail, and I remember we were down there a little while and went before Judge Hosinsky, who said, “Guilty or not guilty.” We said, “Not guilty.” He said, “Dismissed. By the way,” he said, “erase that arrest from their records.” This fellow said, “I was a freshman here, and I was never so impressed in my life. You had a lot of guts.” I said, “Either that or I was a little bit nutty.” /Laughs/ Probably both.

It was a great place to go to school, I’ll tell you that. And my daughter just graduated from there this year. She put in her four years. Lived in the same residence hall where I used to live. Of course, it’s changed a little bit, the girls are there. It’s a good thing they weren’t there when I was there! But the story that goes with it is to have your child go to that same school–and they didn’t have girls until about twelve years ago. She wouldn’t go to any other school. She wanted to go to Notre Dame. I’ve had a great life.

Doggone, the Lord has been good to me. I’ve had nothing but good. That’s all from my background as a kid. I left home to go to Notre Dame and I didn’t go back except to see my father and mother.

Before my grandfather died I went into the war, and that’s kind of a story that tells you what there was between he and I. My grandmother had died earlier. But my grandfather was alive when we came back into Seattle from Honolulu with casualties and people who had to go to hospitals from Hawaii. We had taken troops out and came back with these ambulatories, as we called them. We got into Seattle, oh I guess it was about two o’clock, tied up at the pier, and I took a cab and went up to see my grandfather. He was ninety-six or ninety-seven, and he was lying there on the couch. He had just had his lunch. I went up there, and unless you’re German you probably won’t understand this, but he got my hand and held my hand–we always did that, we were great hand-holders. He held my hand and said, “Oh, it’s so good to see you back.” I said, “Well, it’s over now, everything’s going to be all right.” He said, “Oh, I worried so much about you, all the time it was going on.” But he said, “I’m glad to see you back.”

Well, lo and behold, I went back to the ship, because I had to do some checking, and I came back about seven o’clock, and I got back and he had died. The nurse said, “He said, ‘Just tell Nordy I’m happy and everything is peaceful’, and he just went to sleep.” Everybody said the only reason he kept on going was because I had not come home, and he wanted to see that I was all right. That’s the kind of a thing that sticks with you, and gives you an idea of what kind of a family it was. We had a real great family, they were really terrific, cousins and aunts and uncles. When I think of those things, and think how lucky I was to have that kind of chance to get raised with that kind of people around me all the time, you’ve got to do some good in the world, you can’t be all bad, because they were all good.

Rockne the Motivator

Rockne was one of thespecial people in my life. Rockne was a motivator. He was a man who was teaching you, although he was teaching you football, he was teaching you that football is an experience in which youare now progressing beyond college and are walking into life. He was the other man who drummed into us, day after day, that those people who are here and are less fortunate, you ought to stop and listen. He said, “Never walk away from somebody who tries to tell you something, because he might be asking for help.” I’ll never forget that. I’ve thought that all my life.

About two years ago, you know what’s happened here since they fixed that place up for the people who don’t have homes, Mitch Snyder’s thing [shelter sponsored by the Community for Creative Non-Violence]. We have a lot of people who come up here and they’re asking for hand-outs. God bless them, they’re having a tough time. There was a lady across the street, and I was across the street, but I was in a hurry because I had to get downtown for a meeting. She tried to stop me and I just brushed her off and got in a cab, and then I said, “Oh my god, what have I done.” I said to the cab driver, “Go around the block.” She was still standing there. I said, “Lady, I’m sorry, I walked away from you and you were trying to say something, what was it?” She said, “I’m hungry.” So I gave her some money and said to the cab driver, “We’re all right now.” She said, “You mean you came all the way back? God will always bless you,” and waved. Now that was what Rockne taught me. You ask me what he taught me, he taught me to always listen when somebody is in real trouble. You may walk away from somebody who’s going to jump out of a building, and if you’d have stopped to talk to them maybe it would have made a difference.

Rockne was a teacher that didn’t embarrass you in front of anybody else. Whatever he took up with you, he took up with you. One example of that was at one point in time we had played a game on Saturday and Tom Conley, and Marty Brill, and I think Johnny O’Brien and I had gone to a speakeasy to have some beer. It was right at Notre Dame Avenue, and there was a drugstore right at that particular point, where Rockne’s car was parked when we came out and raced to get the streetcar, so we’d get back in time for dinner. Everybody said, “Oh, he saw us.” I said, “Hey, he didn’t see us, no problem.”

The next day, when everybody who had played the day before was supposed to take it easy, he told everybody not to wear pads except four people, and he named the four of us. He never said a word to us, but he scrimmaged us on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday. The four of us scrimmaged for four days before another game, and we were tired. That night he said, “I’d like the four of you to stay here.” So the four of us stayed there. He said, “Gentlemen, I hope that that beer is sufficiently worked out of your system.” That’s all that was ever said, but he taught us a lesson. We never went back for beer the rest of the time we were in there! That’s the way he taught you. He taught you individually, and he didn’t make it general public information.

He was a perfectionist, and he wanted you to be a perfectionist. I think the best story of that was told by my father, and by Rockne the night before he left. He came back from Seattle and he’d seen my father. My father told me this story too. He said that Rockne was out there to speak for the Studebaker Corporation, and all the dealers west of Denver were in the hotel in Seattle. My father went up to the head table afterwards and he said, “Mr. Rockne, I’m Nordy Hoffmann’s father.” So Rockne reached in his pocket and gave him his key and said “Go up to my room, I’ll see you in a little while.” After he got through he came up and said, “Oh, it’s so good to see you.” And they talked and yakked. And he said, “Have you got a problem, Mr. Hoffmann?” He said, “Yes, I have. I think my son is becoming conceited.” Rockne looked at him and said, “Mr. Hoffmann, don’t worry about that. He is not conceited. He is justifiably proud that he can do that job better than anybody else, and let me tell you, Mr. Hoffmann, he can. And he knows it. But that is not conceit. We knock conceit out of them in one play.” My father told me this story and Rockne told me this story, so I know it jives, it wasn’t something he just made up. That’s typical of Rockne. Rockne was as proud of whatever I could do as if I had been his own son. He was that kind of a man.

He was a perfectionist, and he wanted you to be a perfectionist. I think the best story of that was told by my father, and by Rockne the night before he left. He came back from Seattle and he’d seen my father. My father told me this story too. He said that Rockne was out there to speak for the Studebaker Corporation, and all the dealers west of Denver were in the hotel in Seattle. My father went up to the head table afterwards and he said, “Mr. Rockne, I’m Nordy Hoffmann’s father.” So Rockne reached in his pocket and gave him his key and said “Go up to my room, I’ll see you in a little while.” After he got through he came up and said, “Oh, it’s so good to see you.” And they talked and yakked. And he said, “Have you got a problem, Mr. Hoffmann?” He said, “Yes, I have. I think my son is becoming conceited.” Rockne looked at him and said, “Mr. Hoffmann, don’t worry about that. He is not conceited. He is justifiably proud that he can do that job better than anybody else, and let me tell you, Mr. Hoffmann, he can. And he knows it. But that is not conceit. We knock conceit out of them in one play.” My father told me this story and Rockne told me this story, so I know it jives, it wasn’t something he just made up. That’s typical of Rockne. Rockne was as proud of whatever I could do as if I had been his own son. He was that kind of a man.

He wanted to help you be a better person when you got out of school. He was teaching you all these little things, which probably most people wouldn’t even look at. We had a guy by the name of Dick Donahue, who’s still alive. Dick was always late for practice. There was a big clock up on the tower there and at a quarter after four you were supposed to be there. One day we were out there and Donahue hadn’t come out yet. We were all getting in a big round circle for calisthenics, that’s the way we started to practice. Lo and behold, the gate opens on Cartier Field, and in comes Dick Donahue, and he lumbers across. Rockne waited until he got right up there and he said, “Thank you, Mr. Donahue, for coming for practice. We can begin now that you’re here.” Donahue was never late again for practice. That was his way of teaching somebody.

He would go out of his way to help people. He said that if the people had the desire to do it, he could give them the tools, which he could. He gave it to us, there’s just no question about it. What the hell did I know about football? I’d never played it. And to go to play at a place like Notre Dame? Why, it had to be somebody, and it wasn’t me, I’m telling you that. He drilled motivation in, and he wanted to prepare you for life. This was only a stopgap as far as you were concerned, but it was something that would make a contribution into making you a better or a whole person when you got out of school. I don’t know what more I can say about the man, except that he was just one of the most wonderful men I ever knew. He had a tremendous effect–he still has an effect on us.

I just recently went to South Bend when they had the Rockne Hundredth birthday stamp unveiling, and I was asked by President Reagan to go out with him on Air Force One, so I did. It was a big day as far as I was concerned, because this memorialized a man whom I felt was really worthy of it. Going back and thinking about what he had done for me as a kid, not that I ever became anything great, but I mean, his greatness in being able to diagnose what turns you on and off, to me that is the greatest thing in the world. But that’s the way he was. He was always, always a gentleman. Rockne said in 1929 we were the ramblers, because we had no stadium and so we traveled. All our games were on the road.

The stadium burned down and they were building the new stadium, which is there now. He said, “You are playing for a great university and you ought to look the part.” He said, “The traveling squad will not wear sweaters, they will not wear tee-shirts, they will come out with a tie and coat (he called it a jacket), and you’ll be dressed that way when you’re going anyplace representing the Notre Dame football team.” We went to go out of Plymouth one time, I think we were going to play the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and three guys came down in sweaters. Now, these were three starters, whose names I would not reveal to you or anybody else, and these three starters Rockne took a look at them before the train got in and said, “Manager, would you take these gentlemen back to the campus and get their jackets and their ties. Now, if you can’t make it back here in ten minutes, don’t bother coming back.” They never made the trip. That’s how he taught people a lesson. He felt that if you were going to be good enough to play for Notre Dame, you were representing a great university and ought to look like it. That’s what he made you do.

(Knute Rockne All-American )is pretty accurate from the standpoint of George Gipp, and O’Brien did a good job in that movie also. It was realistic, there’s no question about it. There was a lot of stuff they threw in that probably didn’t belong, but by and large it was accurate It was a good movie and it told something about him.

Pep Talks

Those were great. He gave those. I’ll never forget Southern Cal. We were playing Southern Cal in 1930. Southern Cal was undefeated and we were undefeated. We were goin g to the coast and we were kind of a beaten up team. We had a lot of injuries. He looked at us. There was a training table and I was sitting right at the bottom of the training table and he was standing over there looking at us. He said, “Gentlemen, I salute you. You’ve done everything. You’ve won for the university, you’ve won for Our Lady, you’ve done everything you possibly can. It’s just too much to ask you to go out and win another one. Just go out and play like men and don’t worry about anything because in my book you’re the greatest bunch of men I have ever seen.” Then he stopped and he said, “There is one thing I would ask of you. Moon Mullins” (who was a full-back) “comes from Alhambra” (which is out in Los Angeles). And he said, “If you would get fourteen points in the first half, I would let Moon start the second half, because there’s thirty thousand people from Alhambra in here just to see him play.” Well, we tore off the locker room door going out of that place. We went out and scored twenty-eight points–and they called two touchdowns back in the first half.

g to the coast and we were kind of a beaten up team. We had a lot of injuries. He looked at us. There was a training table and I was sitting right at the bottom of the training table and he was standing over there looking at us. He said, “Gentlemen, I salute you. You’ve done everything. You’ve won for the university, you’ve won for Our Lady, you’ve done everything you possibly can. It’s just too much to ask you to go out and win another one. Just go out and play like men and don’t worry about anything because in my book you’re the greatest bunch of men I have ever seen.” Then he stopped and he said, “There is one thing I would ask of you. Moon Mullins” (who was a full-back) “comes from Alhambra” (which is out in Los Angeles). And he said, “If you would get fourteen points in the first half, I would let Moon start the second half, because there’s thirty thousand people from Alhambra in here just to see him play.” Well, we tore off the locker room door going out of that place. We went out and scored twenty-eight points–and they called two touchdowns back in the first half.

We were just alive, and he started Mully in the second half, as he said he would. He had us so high we could have walked on top of that stadium without even touching the ground. We were ready to go because here was a guy we loved, we’d played with him, and Rock said we ought to do one for Mully. And Mullins was a very popular guy. Moon went out and started the second half, and somebody hit him too hard, and Bert Metzger took him to task out on the field, didn’t cause any problems, but that’s the way he motivated us. How he got our team back up is a longer story.

Tucson, Arizona, when we were playing there. I might as well tell you this, because it gives you an idea of the man. We were at the University of Tucson and we went to work out. Tom Conley and Marty Brill–I always say these guys together because we were always together, we were just buddies–we went out to the field and one of us tried the dressing room door (there were big doors on both ends where we were supposed to dress). I don’t know whether it was Tom or it was Marty who tried the door and said, “The door’s not open.” I said, “Well, how far is it from those mountains down to here?” Well, Tom was the captain. First thing, the guys didn’t even look at the door, they came out and watched us. Rockne comes out, and we were supposed to be dressed and on the field at ten o’clock, it’s now ten-twenty and we’re not even dressed because the door wouldn’t open. Rockne came in the dressing room and the door’s open–it was just stuck. He said, “Get dressed.” We got out on the field and he said, “Gentlemen, I’ve called you together to tell you: I have phlebitis and I think I’m going to get the evening train and go back to Chicago. You don’t need me, you’re not listening to me.” As a result of this, everybody just hung their heads.

Well, I think we had seven defenses against Southern Cal, and we had our offenses, and so Marty spoke up and he said, “Mr. Rockne,”–we always called him Mr. Rockne–“give us another chance.” He said, “That was tough that that door stuck, but why should I give you another chance? I’m not going to get another chance with phlebitis.” We said, “Please give us one more chance.” He said, “All right, I’ll give you one more chance. We will be back out on the field at one o’clock. Go back to the hotel, get your lunch, and be back out here at one. I will question every member of the offensive and defensive teams” (we had to play offense and defense, we didn’t have two ways to go then) “and anybody misses a question, I’m going to get on that train.”

I tell you, we went back and we studied every defense and every offense. He questioned every single guy on that traveling squad, and nobody missed a thing. He said, “Okay, I’ll go to California with you.” That’s where the football game was won, just on a stuck door. This is what it was. It wasn’t planted, because we didn’t know the door was stuck, but that’s how he turned that around to make it the most important thing there was. That was his ability to do. That’s the way he was.

You’d better believe we were thinking like a team, because if anybody had missed the assignment, the rest of the guys would have killed him. So everybody went back and studied. Nobody ate lunch. They just studied. Boy, I can remember that day, even though it’s been a long time.

He was sick one game and Tom Lieb took us to play Northwestern. He was assistant coach at the time, and Bonnie, his wife, sent a wire to us to do good. Lieb got the telegram and got all welled up and said, “I can’t read it, I’m crying.” Moynihan was the center, and Moynihan said, “Give it to me, I can read English.” So he read it, and it was the thing that turned the football game around.

The telegram said: “Please do your best for Rock.” He did have a lot of stories that he gave you. Most of the stories were true stories. He knew how to motivate people, like the thing at California. You know, you’ve done everything you could and we don’t want you to think you have to go out there and win again, and we were dying to win because we wanted the championship. But he wanted to see if that would just kind of eat at us a little bit, and then he gives us this bouquet of roses, Moon Mullins, to go on. Then he gives you the thing about learning all the plays offensively and defensively.

Some of the guys had not been doing too well in that, and it was lousing up our formations, so he made everybody go back and study them. And he knew that we would kill the guy that didn’t know, because Rock would have done back. I mean, that’s the way he did. It was just remarkable the way he could sense what was in your minds. He just did it so beautifully.

On the Death of Knute and Going Undefeated

In ’29 and ’30. Ran though both seasons.And he was killed March 31, 1931, after we had completed those two seasons. I played one year afterwards. Probably the worst blow I’d ever had, up to that point, because the man was so close to all of us. I tell you, you couldn’t believe walking across that campus at noon when we found out that he had been killed in that airplane crash.It was just an unbelievable thing, in Biszar, Kansas. It was a very, very sad day for all of us, and it stayed sad for a long time. It was one of the biggest funerals I’d ever seen. Well, the Lord knew why he wanted him. He had just become a Catholic not too long before that. He had a rosary bead in his hand, and he was going to California to talk about “The Spirit of Notre Dame,” they were going to make the movie. And that’s where he got lost. It was a very sad day for all of us.

In ’29 and ’30. Ran though both seasons.And he was killed March 31, 1931, after we had completed those two seasons. I played one year afterwards. Probably the worst blow I’d ever had, up to that point, because the man was so close to all of us. I tell you, you couldn’t believe walking across that campus at noon when we found out that he had been killed in that airplane crash.It was just an unbelievable thing, in Biszar, Kansas. It was a very, very sad day for all of us, and it stayed sad for a long time. It was one of the biggest funerals I’d ever seen. Well, the Lord knew why he wanted him. He had just become a Catholic not too long before that. He had a rosary bead in his hand, and he was going to California to talk about “The Spirit of Notre Dame,” they were going to make the movie. And that’s where he got lost. It was a very sad day for all of us.

He had greatness in himself and he transmitted to you the fact that you ought to be proud that you were there, and proud that you wereplaying for Notre Dame. That all worked on our minds, it was a very, very difficult problem that we had to handle. We did handleit, and we came out very well after it was over, because I think most of us felt that’s the way Rock wanted us to go. Rockne always will be a legend, and a strange part of it is that all those young men that were on that football team, we never called him anything but “Mr. Rockne.” Not coach, not Rockne, not anything, only Mr. Rockne. We had that kind of respect for him. Now for kids the ages we were, I was about eighteen or nineteen, and some were younger and some were older, we all had that same respect for him. That is a lot to say about the man.

He had greatness in himself and he transmitted to you the fact that you ought to be proud that you were there, and proud that you wereplaying for Notre Dame. That all worked on our minds, it was a very, very difficult problem that we had to handle. We did handleit, and we came out very well after it was over, because I think most of us felt that’s the way Rock wanted us to go. Rockne always will be a legend, and a strange part of it is that all those young men that were on that football team, we never called him anything but “Mr. Rockne.” Not coach, not Rockne, not anything, only Mr. Rockne. We had that kind of respect for him. Now for kids the ages we were, I was about eighteen or nineteen, and some were younger and some were older, we all had that same respect for him. That is a lot to say about the man.

F. Nordy Hoffmann died in Washington, D.C., on April 5, 1996, at the age of eighty- six.

F. Nordy Hoffmann died in Washington, D.C., on April 5, 1996, at the age of eighty- six.

Joe Libby says:

Nordy was a giant man. I knew him the DC area foir over 30 years. A man I will never forget.

Joe Libby

Jason Wilson says:

This story is very telling. The story of the kids sneaking a beer shows that kids in the 1920’s were still kids. The fact that Rock got these kids to play for more than just themselves (and nowadays the NFL draft) or for their coach’s benefit (i.e., a new, multi-million dollar contract) but for their university and each other exemplifies just how uniquely difficult it is to find true leadership in coaching. This isn’t terribly surprising, since there are so few universities that have an aura beyond the bricks and mortar comprising them. Holtz was the last one coach in college to have realized the value of ND’s aura and used it. Holtz is the last one to transcend Rock’s leadership qualities. That’s why he is the only coach to have a national platform in the Dr. Lou show on ESPN. He is special. Let’s hope ND has found a successor to Rock and most recently Lou in Brian Kelly.

Vince Mackiel says:

Thanks for posting Mr. Hoffman’s memories.

Jim Finnegan says:

As a 1956 graduate of ND, and a one year walk on (fall of 1952) under coach Frank Leahy, I have always held dear the ND football aura. Nordy as a Democrat before the Democrat family left me, makes me wonder if Nordy spoke out against the great evil of abortion on demand during his time in office. So many great men of stature seem to lack the “courage” when in positions of authority and very visable and important positions whose voice can make a difference, choose to stay silent. Hopefully Nordy had the same courage on the life or death issue of abortion on demand that the Democratic party has accepted as their position, as he did on the fields of play at ND. What a nice story and insight to early days of football at ND>

Vince Mackiel says:

The history and story of Notre Dame grows on me.

Phil Eck says:

Wonderful story

Can I get a copy of the first picture?

Standing next to Rockne is my Grandfather Fred Miller.

ted sheehan says:

nordy,just another example of the lore of notre dame……

Joe says:

I have a whole set of these notre dame football cards (as shown).

Drue Johnson says:

I am not a Roman Catholic, but I married one and sent my first born into the Notre Dame family. There is no place like it, for reasons far beyond football. It is a breath of fresh air to hear Brian Kelly talk about playing for Notre Dame and Our Lady. In his “right kind of guys” mantra, which I totally embrace, he must look into a players eyes and see the spirit of Nordy Hoffman and the ilk. It is what is in the heart that makes players play a step above what is expected, not the stars behind the name.

There are kids out there who have that kind of heart, and I hope Brian Kelly can find them again and guide them down the path of Nordy Hoffman.

ND is indeed a magical place, a special place, like no other. It is hard to understand for today’s athletes just what that means….what that can do for them…..and what they can do for the world.

John Adams says:

Nordy was a real Notre Dame Man. His widow, Joanne, still lives in their home in my neighborhood in Potomac, MD. I am making sure she sees this article. She is a class act too.

Jim Meko '68 says:

I first met Mr. Hoffman in 1977, while I was employed at the Justice Department. He quickly became my role model…the consumate Notre Dame man…kind, caring, compassionate, professional and on top of every detail. It was an honor to know him and to learn from him. I must confess that I got goosebumps every time I heard that absolutely unique fellow “Domer” announce to Congress the entrance of the President of the United States! Nordy Hoffman was and is a National and a Notre Dame original! May he rest in peace in the presence of God and Notre Dame, Our Mother.

Mike says:

Thanks for posting this story with my Great Uncle Nordy. I don’t remember ever meeting him, but my family is still very proud of him and I am honored to have joined him as a Notre Dame Alum.

Joe Libby says:

I have written earlier, but as I read the comments about Nordy, I had to share two stories about him. One I witinessed personally, the second I heard either from Nordy or one of his friends. In 1977, Nordy was asked to introduce Senator Lugar, at a ND luncheon. One of the senator’s opening remarks were, You see him and you see me, now you realize who is the real senate boss, as Nordy stood bside the Senator and towered over him.

The second story was when Nordy was going to be inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. President Reagan was to be the key speaker. Nordy was asked to greet the president. He was being kidded by Senators Laxalt and Baker on how he was going to address the president. What would he call him, Mr. President or Govornor. When Reagan arrived, he quickly acknowledged Senators Baker and Laxalt, and turned to Nordy. Nordy quickly responded by giving Reagan a bear hug and said HOW ARE YOU DOING GIPPER!

All of us who had the opportunity to know him still miss him. His humor and leadership had a great impact on our local ND alumni. His door was always open to all ND grads, whether they were Democrats or Republicans. One thing is certain, bitterness that exists between both parties today, Nordy would have put a stop to.

One of my biggest regret is that in 1994, Nordy spoke to the local club for the last time about Rockne. We did not video tape this talk for all ND alumni..

Joe Libby